Attention: Restrictions on use of AUA, AUAER, and UCF content in third party applications, including artificial intelligence technologies, such as large language models and generative AI.

You are prohibited from using or uploading content you accessed through this website into external applications, bots, software, or websites, including those using artificial intelligence technologies and infrastructure, including deep learning, machine learning and large language models and generative AI.

Vasectomy: AUA Guideline (2026)

Using AUA Guidelines

This AUA guideline is provided free of use to the general public for academic and research purposes. However, any person or company accessing AUA guidelines for promotional or commercial use must obtain a licensed copy. To obtain the licensable copy of this guideline, please contact Keith Price at kprice@auanet.org.

Unabridged version of this Guideline [pdf]

Appendices for this Guideline [pdf]

Vasectomy Occlusion Techniques [pdf]

To cite this guideline:

Schlegel PN, Clark JY, Coward , RM, et al. Vasectomy: AUA Guideline Part I. J Urol. 0(0). Doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000004861. https://www.auajournals.org/doi/10.1097/JU.0000000000004861

Schlegel PN, Clark JY, Coward , RM, et al. Fertility Restoration After Vasectomy: AUA Guideline Part II. J Urol. 0(0). Doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000004862. https://www.auajournals.org/doi/10.1097/JU.0000000000004862

Panel Members

Peter N. Schlegel, MD; Joseph Y. Clark, MD; R. Matthew Coward, MD; Steven J. Hirshberg, MD; Stanton Honig, MD; Wayland Hsiao, MD; Michel Labrecque, MD, PhD; Richard Lee, MD, MBA; Jonathan Stack; Cigdem Tanrikut, MD; Peter Tiffany, MD; Sarah C. Vij, MD; Akanksha Mehta, MD, MS

Consultants and Staff

Jonathan R. Treadwell, PhD; Erin Kirkby, MS

Illustrator

Divya Lagisetti

SUMMARY

Purpose

This Guideline aims to provide a contemporary overview of vasectomy, including a discussion of indications, pre-operative counseling and preparation, peri-operative considerations, procedural techniques, potential risks and complications, and post-operative care, to ensure that healthcare providers offer accurate, evidence-based information to patients considering this method of permanent contraception. The Guideline also discusses options for future fertility following vasectomy.

Methodology

A comprehensive search of the literature was performed and covered articles published between January 1, 1990 and January 30, 2024. Relevant study designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs), and observational studies (cohort with and without comparison group, case-control). Systematic reviews were searched as an additional resource to identify any relevant studies with the designs noted above that may not have been captured in the literature search.

GUIDELINE STATEMENTS

Patient Evaluation and Counseling

- Clinicians should provide pre-operative consultation for the patient considering vasectomy. (Clinical Principle) Consultation may be accomplished virtually or in person. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- Clinicians should counsel patients that vasectomy is a safe and effective means of permanent contraception. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- Clinicians may inform patients that no causal link has been established between vasectomy and the development of prostate cancer. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

- Clinicians may inform patients that no causal link has been established between vasectomy and development of high-grade prostate cancer or increased prostate cancer mortality. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

- Clinicians may inform patients that no causal link has been established between vasectomy and the risk of cardiovascular disease. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- Clinicians may inform patients that no causal link has been established between vasectomy and nephrolithiasis. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

Peri-Procedural Antibiotics

- Clinicians may forego peri-procedural antibiotics for patients undergoing vasectomy unless the patient is at high risk of infection. (Expert Opinion)

Skin Preparation

- Clinicians should prepare the skin with a sterilizing solution prior to vasectomy. (Clinical Principle) Clinicians may remove hair pre-operatively. (Expert Opinion)

Anesthetics and Peri-Procedural Pain Management

- Clinicians should perform vasectomy with local anesthesia delivered by skin infiltration with a needle and/or jet injector. Topical anesthetic may lessen the pain of local anesthetic infiltration during vasectomy. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- Clinicians should recommend non-opioid oral analgesics (acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatories [NSAID]) for post-operative pain control. (Expert Opinion)

Vas Isolation

- Surgeons should isolate and expose the vas deferens for vasectomy using a minimally invasive approach such as the no-scalpel vasectomy (NSV) technique. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade A)

Vas Occlusion

- Surgeons should perform vasectomy with an occlusive technique that combines mucosal cautery (MC) and fascial interposition (FI). (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

- Surgeons should not perform vas occlusion using only ligation and excision of a short vas segment. (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade A)

- Surgeons may omit routine histological evaluation of excised tissues. (Expert Opinion)

Vasectomy Complications

- Surgeons who perform vasectomy should be able to recognize and treat complications after vasectomy, including bleeding, infection, epididymitis, and chronic scrotal pain. (Clinical Principle)

Post-Vasectomy Semen Analysis

- Patients should provide at least one appropriately collected semen sample following vasectomy to confirm occlusive success. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- An uncentrifuged semen sample following vasectomy may be evaluated in a lab/office setting or by mail-in testing. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- Patients may discontinue contraception following confirmation of complete azoospermia or ≤100,000 rare non-motile sperm per mL (RNMS) from a single uncentrifuged semen sample evaluated within 2 hours of collection. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B) A sample evaluated >2 hours after collection should show azoospermia to stop contraception. (Expert Opinion)

- A post-vasectomy semen sample may be submitted as early as 8 weeks following vasectomy. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Repeat Vasectomy

- In patients with any persistent motile sperm in the ejaculate 6 months following vasectomy, counseling for repeat vasectomy should be offered. In patients with >100,000 non-motile sperm per mL persisting after 6 months, shared decision-making should be utilized to determine whether to repeat vasectomy, continue contraception and/or obtain repeat semen evaluations. (Expert Opinion)

Fertility Restoration After Vasectomy

- Clinicians should inform patients who desire restoration of fertility after vasectomy that surgical reconstruction or surgical sperm retrieval with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) are both options. Counseling should be provided to couples based on their clinical presentation to support shared decision-making regarding options for family building. (Expert Opinion)

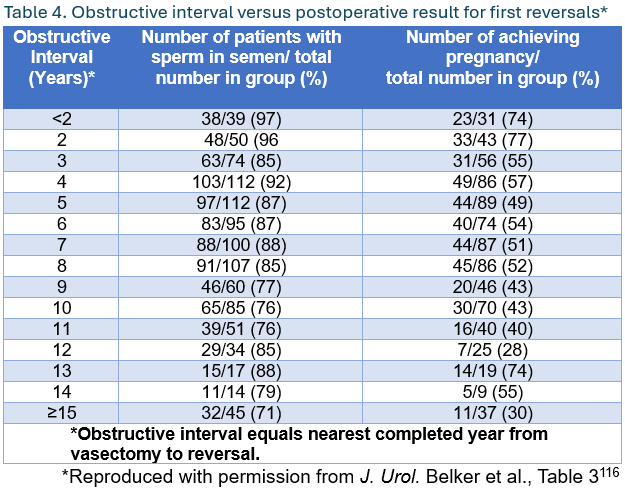

- Surgeons should inform patients considering vasectomy reversal that duration of the obstructive interval, patient age, and female partner age are the best preoperative predictors of post-operative reversal success. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- Surgeons should evaluate vasal fluid microscopically at the time of vasectomy reversal as the presence of sperm at the site of planned reconstruction is the best intraoperative predictor of patency after vasectomy reversal. (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

- Surgeons should perform a microsurgical vasovasostomy using a modified one-layer or a two-layer anastomosis based on surgeon preference. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- Surgeons offering vasectomy reversal should have microsurgical expertise to provide vasoepididymostomy as well as vasovasostomy. (Expert Opinion)

- Surgeons may perform vasoepididymostomy using longitudinal intussusception, triangulation intussusception, end-to-end anastomosis, or end-to-side anastomosis. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

INTRODUCTION

Background

Vasectomy is a safe, minimally invasive, and effective means of permanent contraception for men. With over 500,000 vasectomies performed annually in the United States, it remains one of the most common outpatient procedures performed by urologists.1 A 2021 study using data from the National Survey of Family Growth identified a decline in vasectomy utilization from 2002 through 2017.2 More recent data, however, suggest that vasectomy consultation and procedural volumes have increased more than 150% following the Dobbs v. Jackson ruling by the US Supreme Court in 2022, which overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling establishing abortion as a protected constitutional right.3

This Guideline aims to provide a contemporary overview of vasectomy, including a discussion of indications, pre-operative counseling and preparation, peri-operative considerations, procedural techniques, potential risks and complications, and post-operative care, to ensure that healthcare providers offer accurate, evidence-based information to patients considering this method of permanent contraception. The Guideline also discusses options for future fertility following vasectomy.

METHODOLOGY

Determination of Guideline scope and assessment of the final systematic review to inform Guideline statements was conducted in conjunction with the Vasectomy Guideline Panel. The systematic review utilized to inform this Guideline and methodological support was provided by an independent methodological consultant team from ECRI (founded as the Emergency Care Research Institute).

Panel Formation

The Panel was created in 2023 by the American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc. (AUAER). The Practice Guidelines Committee (PGC) of the American Urological Association (AUA) selected the Panel Chair who in turn appointed the additional panel members following an open nomination process to identify members with specific expertise in this area. Funding for the Panel was provided by the AUA; panel members received no remuneration for their work.

Searches and Article Selection

A comprehensive search of the literature was performed by ECRI. This search covered articles published between January 1, 1990 and January 30, 2024. Relevant study designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs), and observational studies (cohort with and without comparison group, case-control). Systematic reviews were searched as an additional resource to identify any relevant studies with the designs noted above that may not have been captured in the literature search.

Four analysts reviewed the abstracts identified in the literature search. Articles that potentially fulfilled the outlined inclusion criteria and answered one or more of the questions specified by the Panel were retrieved in full text for review by the team. For all full-text exclusions, ECRI recorded the reason for exclusion.

To focus the analysis on the most relevant evidence, ECRI only considered articles published in full after January 1, 1990 in the English language and reporting data for one or more of the Key Questions. For most Key Questions, selected studies had to have included at least 10 patients per treatment arm; the exception being the question pertaining to the association of vasectomy with any medical conditions, which required a minimum of 1,000 patients per study. Systematic reviews were used only as a supplemental source to identify relevant studies that may have been missed by the literature search.

A total of 1,343 articles were retrieved by the search, and ECRI ordered full text for 271 of them for further review. Of these, 157 articles were excluded; the most common reasons for exclusion were: publication as a conference abstract only, lack of inclusion of an intervention or comparator of interest, and study results being superseded by a more recent or comprehensive publication.

Data Abstraction and Synthesis

Information from each article included was extracted by one of four team members (all ECRI analysts) using standard extraction forms. The team lead developed the forms, trained the extractors, reviewed the work of the other extractors, and searched for inconsistencies and missing information in the extracted data.

ECRI performed meta-analyses using Stata when sufficient outcome data from multiple comparative studies of the same study design was available. When meta-analyses were not possible or inappropriate, ECRI conducted narrative syntheses summarizing study findings.

Risk of Bias Assessment

For RCTs, ECRI used a Cochrane Risk of Bias tool to assess risk of bias, whereas for non-randomized comparative studies, ECRI used the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Intervention (ROBINS-I) tool. For assessment of prognostic studies, ECRI used the Quality in Prognosis (QUIPS) tool. The ROBINS-I tool results in ratings of Low, Moderate, Serious, or Critical; for grading purposes ECRI categorized Serious and Critical as “High” risk of bias.

Determination of Evidence Strength

The overall certainty of the body of evidence supporting the findings for the outcomes of interest in this report was assessed using the GRADE system, which involves consideration of the following factors: study limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias across studies. The GRADE system rates the certainty in the evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low. For instance, a body of evidence that consists of RCTs automatically starts with a rating of high certainty. This rating can be downgraded if some of the RCTs have serious flaws such as lack of blinding of outcome assessors, not reporting concealment of allocation, or high dropout rate. Similarly, the certainty can be downgraded if inconsistencies of findings are present or if there is a lack of precision surrounding an outcome’s effect size.

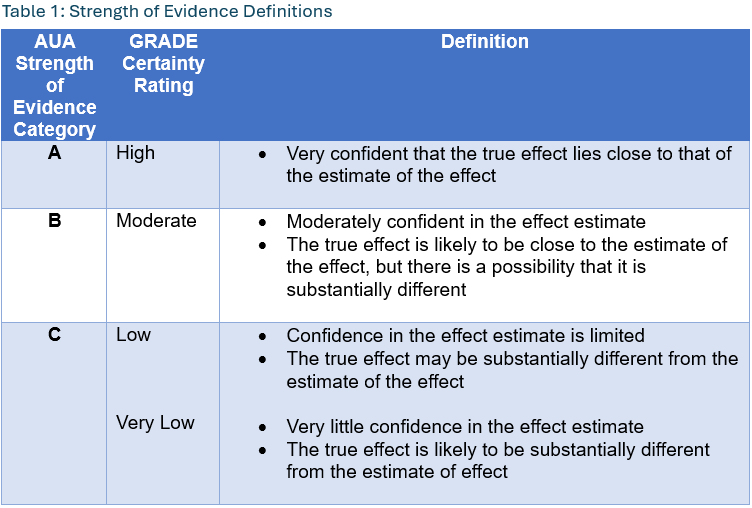

The AUA employs a 3-tiered strength of evidence system to underpin evidence-based guideline statements. Table 1 summarizes the GRADE categories, definitions, and how these categories translate to the AUA strength of evidence categories. In short, high certainty by GRADE translates to AUA A-category strength of evidence, moderate to B, and both low and very low to C.

By definition, Grade A evidence is evidence about which the Panel has a high level of certainty, Grade B evidence is evidence about which the Panel has a moderate level of certainty, and Grade C evidence is evidence about which the Panel has a low level of certainty.4

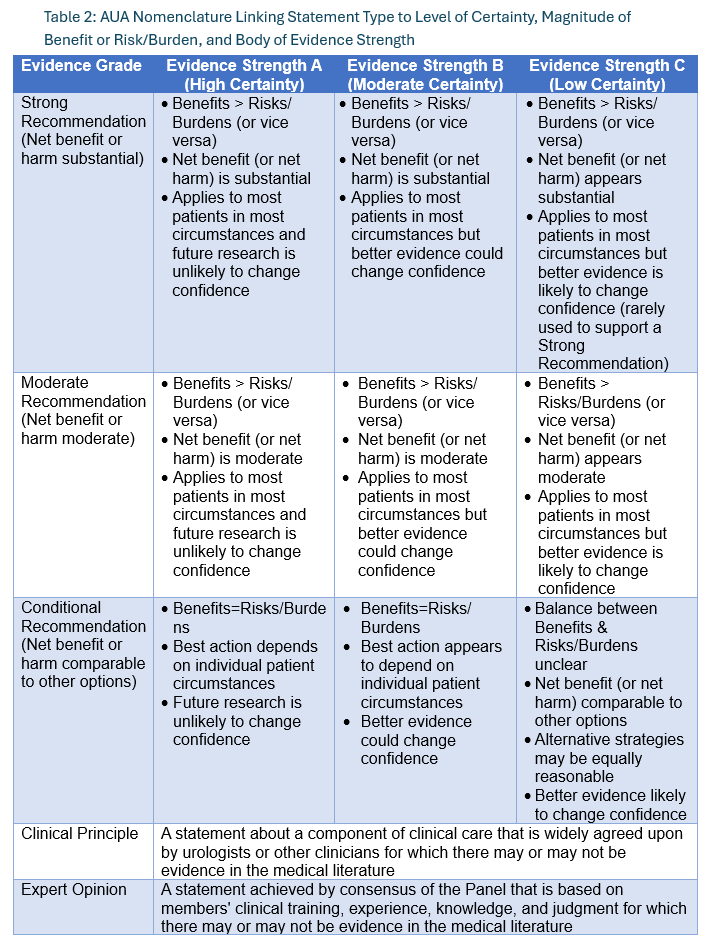

AUA Nomenclature: Linking Statement Type to Evidence Strength

The AUA nomenclature system explicitly links statement type to body of evidence strength, level of certainty, magnitude of benefit or risk/burdens, and the Panel’s judgment regarding the balance between benefits and risks/burdens (Table 2). Strong Recommendations are directive statements that an action should (benefits outweigh risks/burdens) or should not (risks/burdens outweigh benefits) be undertaken because net benefit or net harm is substantial. Moderate Recommendations are directive statements that an action should (benefits outweigh risks/burdens) or should not (risks/burdens outweigh benefits) be undertaken because net benefit or net harm is moderate. Conditional Recommendations are non-directive statements used when the evidence indicates that there is no apparent net benefit or harm, or when the balance between benefits and risks/burden is unclear. All three statement types may be supported by any body of evidence strength grade. Body of evidence strength Grade A in support of a Strong or Moderate Recommendation indicates that the statement can be applied to most patients in most circumstances and future research is unlikely to change confidence. Body of evidence strength Grade B in support of a Strong or Moderate Recommendation indicates that the statement can be applied to most patients in most circumstances, but better evidence could change confidence. Body of evidence strength Grade C in support of a Strong or Moderate Recommendation indicates that the statement can be applied to most patients in most circumstances, but better evidence is likely to change confidence. Conditional Recommendations also can be supported by any evidence strength. When body of evidence strength is Grade A, the statement indicates that benefits and risks/burdens appear balanced, the best action depends on patient circumstances, and future research is unlikely to change confidence. When body of evidence strength Grade B is used, benefits and risks/burdens appear balanced, the best action also depends on individual patient circumstances and better evidence could change confidence. When body of evidence strength Grade C is used, there is uncertainty regarding the balance between benefits and risks/burdens, alternative strategies may be equally reasonable, and better evidence is likely to change confidence.

Where gaps in the evidence existed, the Panel provides guidance in the form of Clinical Principles or Expert Opinions with consensus achieved using a modified Delphi technique if differences in opinion emerged.5 A Clinical Principle is a statement about a component of clinical care that is widely agreed upon by urologists or other clinicians for which there may or may not be evidence in the medical literature. Expert Opinion refers to a statement, achieved by consensus of the Panel, that is based on members’ clinical training, experience, knowledge, and judgment.

Peer Review and Document Approval

An integral part of the guideline development process at the AUA is external peer review. The AUA conducted a thorough peer review process to ensure that the document was reviewed by clinicians with expertise in vasectomy. In addition to reviewers from the AUA PGC, Science and Quality Council (SQC), and Board of Directors (BOD), the document was reviewed by external content experts, who were identified as follows: (a) a call for reviewers was placed on the AUA website from December 10, 2024 to January 3, 2025 to allow all interested parties to request a copy of the document for review, and (b) notifications were sent through various AUA membership and patient advocacy channels to specifically promote the availability of the document for review. The draft Guideline was ultimately distributed to 89 peer reviewers. All peer review comments were blinded and sent to the Panel for review. In total, 42 reviewers provided comments. At the end of the peer review process, a total of 266 comments were received. Following comment discussion, the Panel revised the draft as needed. Once finalized, the Guideline was submitted to the AUA PGC, SQC, and BOD for final approval.

GUIDELINE STATEMENTS

Patient Evaluation and Counseling

Guideline Statement 1

Clinicians should provide pre-operative consultation for the patient considering vasectomy. (Clinical Principle) Consultation may be accomplished virtually or in person. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Guideline Statement 2

Clinicians should counsel patients that vasectomy is a safe and effective means of permanent contraception. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Guideline Statement 3

Clinicians may inform patients that no causal link has been established between vasectomy and the development of prostate cancer. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

Guideline Statement 4

Clinicians may inform patients that no causal link has been established between vasectomy and development of high-grade prostate cancer or increased prostate cancer mortality. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

Guideline Statement 5

Clinicians may inform patients that no causal link has been established between vasectomy and the risk of cardiovascular disease. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Guideline Statement 6

Clinicians may inform patients that no causal link has been established between vasectomy and nephrolithiasis. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

Peri-Procedural Antibiotics

Guideline Statement 7

Clinicians may forego peri-procedural antibiotics for patients undergoing vasectomy unless the patient is at high risk of infection. (Expert Opinion)

Skin Preparation

Guideline Statement 8

Clinicians should prepare the skin with a sterilizing solution prior to vasectomy. (Clinical Principle) Clinicians may remove hair pre-operatively. (Expert Opinion)

Anesthetics and Peri-Procedural Pain Management

Guideline Statement 9

Clinicians should perform vasectomy with local anesthesia delivered by skin infiltration with a needle and/or jet injector. Topical anesthetic may lessen the pain of local anesthetic infiltration during vasectomy. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Guideline Statement 10

Clinicians should recommend non-opioid oral analgesics (acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatories [NSAID]) for post-operative pain control. (Expert Opinion)

Vas Isolation

Guideline Statement 11

Surgeons should isolate and expose the vas deferens for vasectomy using a minimally invasive approach such as the no-scalpel vasectomy (NSV) technique. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade A)

Vas Occlusion

Guideline Statement 12

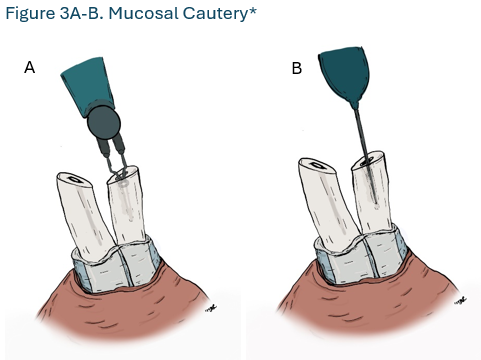

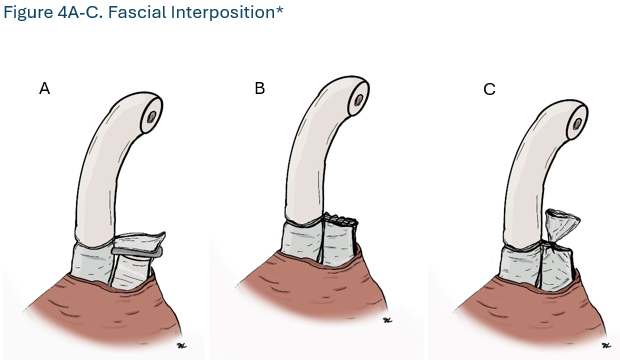

Surgeons should perform vasectomy with an occlusive technique that combines mucosal cautery (MC) and fascial interposition (FI). (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

Guideline Statement 13

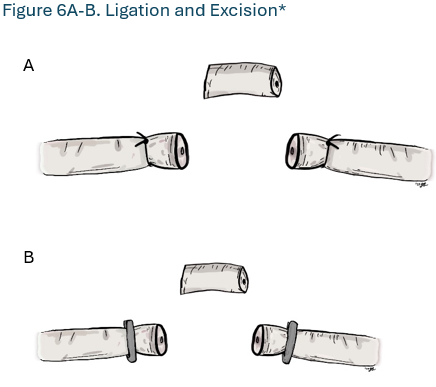

Surgeons should not perform vas occlusion using only ligation and excision of a short vas segment (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade A)

Guideline Statement 14

Surgeons may omit routine histological evaluation of excised tissues. (Expert Opinion)

Vasectomy Complications

Guideline Statement 15

Surgeons who perform vasectomy should be able to recognize and treat complications after vasectomy, including bleeding, infection, epididymitis, and chronic scrotal pain. (Clinical Principle)

Post-Vasectomy Semen Analysis

Guideline Statement 16

Patients should provide at least one appropriately collected semen sample following vasectomy to confirm occlusive success. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Guideline Statement 17

An uncentrifuged semen sample following vasectomy may be evaluated in a lab/office setting or by mail-in testing. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Guideline Statement 18

Patients may discontinue contraception following confirmation of complete azoospermia or ≤100,000 rare non-motile sperm per mL (RNMS) from a single uncentrifuged semen sample evaluated within 2 hours of collection. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B) A sample evaluated >2 hours after collection should show azoospermia to stop contraception. (Expert Opinion)

Guideline Statement 19

A post-vasectomy semen sample may be submitted as early as 8 weeks following vasectomy. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Repeat Vasectomy

Guideline Statement 20

In patients with any persistent motile sperm in the ejaculate 6 months following vasectomy, counseling for repeat vasectomy should be offered. In patients with > 100,000 non-motile sperm per mL persisting after 6 months, shared decision-making should be utilized to determine whether to repeat vasectomy, continue contraception and/or obtain repeat semen evaluations. (Expert Opinion)

Fertility Restoration After Vasectomy

Guideline Statement 21

Clinicians should inform patients who desire restoration of fertility after vasectomy that surgical reconstruction or surgical sperm retrieval with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) are both options. Counseling should be provided to couples based on their clinical presentation to support shared decision-making regarding options for family building. (Expert Opinion)

Guideline Statement 22

Surgeons should inform patients considering vasectomy reversal that duration of the obstructive interval, patient age, and female partner age are the best preoperative predictors of post-operative reversal success. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Guideline Statement 23

Surgeons should evaluate vasal fluid microscopically at the time of vasectomy reversal as the presence of sperm at the site of planned reconstruction is the best intraoperative predictor of patency after vasectomy reversal. (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B)

Guideline Statement 24

Surgeons should perform a microsurgical vasovasostomy using a modified one-layer or a two-layer anastomosis based on surgeon preference. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

Guideline Statement 25

Surgeons offering vasectomy reversal should have microsurgical expertise to provide vasoepididymostomy as well as vasovasostomy. (Expert Opinion)

Guideline Statement 26

Surgeons may perform vasoepididymostomy using longitudinal intussusception, triangulation intussusception, end-to-end anastomosis, or end-to-side anastomosis. (Conditional Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although this Guideline demonstrates substantial progress since the initial publication of the 2012 AUA Vasectomy Guideline, there are many areas where gaps of knowledge persist.

With respect to patient evaluation and counseling, this Guideline addresses the safety and efficacy of vasectomy as a permanent contraception method. For patients in a heterosexual relationship, the decision-making process is highly variable. Despite data showing that vasectomy has a lower failure rate than tubal ligation and is very safe, many couples still decide to proceed with tubal ligation. This occurs both in the United States and around the world. There may be cultural, religious, reliability factors, and access to care that influence these couples in this shared decision-making process. Nevertheless, male patients appear to be taking more responsibility for family planning. Patient education studies could help promote more interest in vasectomy. Education of couples with respect to the value of vasectomy for permanent contraception may aid couples’ decision-making process. Partnering with obstetrics and gynecology colleagues may be beneficial in this process of patient education. In the era of direct-to-consumer care for medical needs, taking information directly to couples may be a better approach to promulgate accurate information on the safety and efficacy of vasectomy.

Patient requests for vasectomy are occurring at an earlier age, and data on patient choice for permanent contraception are limited. The consequences of early vasectomy choice have also not been well studied. Regret regarding vasectomy choice is an area where data are lacking. Regret can be based on post-operative pain, need for reversal, or general regret. Relevant factors may include age less than 30, lack of information about reversibility, high impulsivity score, lower education level, involvement with a responsible partner, and child status.133

The published literature speaks volumes about the utilization of MC and FI in techniques for vas occlusion. Published data with only ligation and excision have shown much higher failure rates, although these techniques have historically been commonly used for vasectomy in the United States. One goal of this Guideline is to promulgate information on the effectiveness of MC and FI for vas occlusion.

Large well-designed studies on failures and complications are needed to evaluate outcomes after:

- Extensive electrocautery (MSI technique with or without division) versus MC and FI

- Mucosal electrical versus thermal cautery

- MC with and without FI

- FI technique (clips, free tie, suture with needle)

- FI without MC with and without folding back of one or both segments

- Open-ended versus closed-ended vasectomy

- Excision versus no excision of vasal segments

Further, there is a need for well-designed observational studies on how the differences encountered when performing the same technique (e.g., length of cauterized vas segment and volume of tissues included in FI) influence the risk of failure and of complications (non-infectious inflammation, painful granuloma, and congestive epididymitis).

PVSA testing is probably one of the most controversial topics in vasectomy care at the time of writing this Guideline. Compliance with obtaining PVSA samples is far from 100% in routine practice. Analysis of fresh versus “mail-in” and laboratory versus “home testing” are both areas that are evolving. The current Guideline changes the paradigm to allow evaluation of semen samples more than 2 hours after collection with mail-in testing.

If failure rates are so low for occlusive techniques such as combined MC and FI, is a PVSA needed? Failure rates without PVSA testing are similar to those achieved with perfect use of oral contraceptives (99%) and far better than with typical use of oral contraceptives (91%).134 Some patients may be willing to accept the low risk of pregnancy after vasectomy alone when given this information rather than pursue PVSA.

If one agrees that PVSA is recommended, then optimizing compliance becomes important. As stated in the body of the Guideline, data are conflicting on whether the availability of home semen analysis kits increases compliance with PVSA testing.

In addition, many variables can affect whether a patient provides a PVSA. Future studies evaluating factors like “providing a cup,” scheduling a post op visit, travel distance for fresh semen analysis, method of PVSA testing, test location (home versus lab), timing of test (fresh versus mail-in), increased “touch points” or reminders via email/text to complete the test, and pre-procedure payment for testing, will all be important to consider in order to optimize compliance with PVSA .95, 135, 136 Lastly, patient comfort with “relative risk” of failure using non-azoospermic criteria for clearance need to be addressed.137 What are the failure rates with 250,000 RNMS, 500,000 RNMS or 1 million RNMS? Shared decision-making between the provider and patient for relative risks based on hard data will be important in the future. At present, most studies report about a 50% compliance rate for a single PVSA. Optimization of compliance is critical to assess overall vasal occlusive rates and allay fears of some patients.

There is no discussion in this Guideline on non-surgical male contraceptive options. This area of research includes less invasive procedures, as well as hormonal and non-hormonal male contraceptive protocols that are experimental to-date.138 Hormonal agents investigated include 7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone (MENT), DMAU, 11β-MNTDC, and the combination of segesterone acetate with testosterone in gel form. These agents show promise due to their ability to suppress the gonadotropins FSH and LH, resulting in suppression of spermatogenesis with minimal side effects. Rebound of sperm production after treatment has also been studied. Among the agents evaluated, oral DMAU, 11β-MNTDC, and the segesterone acetate–testosterone gel have the greatest potential for male hormonal contraception since they are efficacious, easy to administer, highly reversible and have favorable safety profiles. Phase 3 hormonal contraception trials are in progress.139

Non-hormonal contraceptive approaches are topics of active investigation. They target key elements of spermatogenic function, including the acrosome reaction (e.g., with ADCY inhibitors), basic spermatozoal function (e.g., BRDT, HIPK4), and disruption of sperm production, (e.g., with retinoic acid antagonists).140 Most of these agents have only been tested in pre-clinical models, and issues regarding effectiveness, reversibility and tolerability have not been fully investigated.

Interventional procedures including percutaneous intra-vasal injection of hydrogel and other materials have the ability to induce short- or long-term contraception without surgery. These procedures include reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance (RISUG) that results in gel binding to the wall of the vasal lumen, with the injected agents disrupting the membrane of spermatozoa, disabling enzymes involved with fertilization, and resulting in only dysfunctional spermatozoa in the ejaculate.141 The implant can be reversed by intra-vasal injection of another substance to remove the gel. A similar hydrogel with complete blockade of the vas lumen and possibility of removing the gel, and a shorter acting hydrol with efficacy for two years are under development in USA.

This Guideline addresses restoration of fertility after vasectomy for the first time. A review of the pertinent literature on this topic identified some important issues that will need to be delineated in the future. There are no published data regarding what microsurgical expertise is necessary to provide vasectomy reversal surgical care; as such, this information is provided as Expert Opinion in this Guideline. With this gap in knowledge, success rates of vasoepididymostomy are based mostly on single series with non-randomized data to evaluate results. Many practitioners who perform only vasovasostomies might report their data of outcomes with vasovasostomy despite typical indications for need for vasoepididymostomy, such as increased obstructive interval, no sperm seen with vasal fluid sampling, inspissated vasal fluid at time of reversal, and epididymal induration. In addition, a single surgeon randomized trial of different microsurgical techniques would be valuable to determine if one technique is better than the others. Although expertise in vasoepididymostomy is recommended for the surgeon offering vasectomy reversal, the number of urologists with such expertise in the United States is limited. Many urologists offering vasectomy reversal today do not have training or experience in performance of vasoepididymostomy despite the value of this procedure for a substantial number of men undergoing attempted vasectomy reversal.

What is the best option for fertility after vasectomy? There are limited data in comparative trials to assess different interventions, and assisted reproduction as well as microsurgical reconstructive results can vary greatly at different centers. Further, a randomized trial may be difficult to accrue. However, a randomized trial comparing vasectomy reversal versus sperm retrieval and ICSI would be a valuable study. This would need to be performed in a health system that offers both options without cost limitations and control for patient and partner age/type of anastomosis (vasovasostomy versus vasoepididymostomy) and delay of cross-over for periods of time that may limit patient acceptance.

Finally, this Guideline addresses post vasectomy pain syndrome as part of the preoperative counselling of patients considering vasectomy. The incidence of post vasectomy pain syndrome that is persistent and affects QOL is typically reported to be about 1-2%.142 This important topic is addressed in the AUA Guideline on Chronic Pelvic Pain (Part III).88 Reassurance and good bedside manner are important elements of maintaining an effective patient-physician relationship for management of this syndrome. Future studies directed towards identifying the cause(s) of pain, diagnostic evaluation and effective treatment are needed.

TOOLS AND RESOURCES

ABBREVIATIONS

| 95% CI | 95% confidence interval |

| ART | assisted reproductive technologies |

| ASRM | American Society of Reproductive Medicine |

| AUA | American Urological Association |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| CCT | controlled clinical trial |

| FI | fascial interposition |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| ICSI | intracytoplasmic sperm injection |

| IUI | intrauterine insemination |

| IVF | in vitro fertilization |

| IVT | incisional vasectomy technique |

| LIA | local infiltration of anesthesia |

| MC | mucosal cautery |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| MIV | minimally-invasive vasectomy |

| MSI | Marie Stopes International |

| NSAID | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| NSV | no-scalpel vasectomy |

| OR | odds ratio |

| PGC | Practice Guidelines Committee |

| PVSA | post-vasectomy semen analysis |

| QOL | quality of life |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| RISUG | reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance |

| RNMS | rare, non-motile sperm |

| RR | relative risk |

| SCB | spermatic cord block |

| SQC | Science & Quality Council |

| SSI | surgical site infection |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

REFERENCES

- Ostrowski, K. A., Holt, S. K., Haynes, B. et al.: Evaluation of Vasectomy Trends in the United States. Urology, 118: 76, 2018

- Zhang, X., Eisenberg, M. L.: Vasectomy utilization in men aged 18-45 declined between 2002 and 2017: Results from the United States National Survey for Family Growth data. Andrology, 10: 137, 2022

- Zhu, A., Nam, C. S., Gingrich, D. et al.: Short-Term Changes in Vasectomy Consults and Procedures Following Dobbs v Jackson Women's Health Organization. Urol Pract, 11: 517, 2024

- Faraday, M., Hubbard, H., Kosiak, B., Dmochowski, R.: Staying at the cutting edge: a review and analysis of evidence reporting and grading; the recommendations of the American Urological Association. BJU Int, 104: 294, 2009

- Hsu, C.-C., Sandford, B.: The Delphi Technique: Making Sense Of Consensus. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 12, 2007

- Hernandez, H., Bernstein, A. P., Zhu, E. et al.: No detectable association between virtual setting for vasectomy consultation and vasectomy completion rate. Urol Pract, 11: 72, 2024

- Doolittle, J., Jackson, E. M., Gill, B., Vij, S. C.: The omission of genitourinary physical exam in telehealth pre-vasectomy consults does not reduce rates of office procedure completion. Urology: 19, 2022

- Jahnen, M., Rechberger, A., Meissner, V. H. et al.: Associations of vasectomy with sexual dysfunctions and the sex life of middle-aged men. Andrology, 13: 665, 2025

- Tasset, J., Rodriguez, M.: "Permanent" Contraception - Reexamining Modern Tubal Sterilization Effectiveness. NEJM Evid, 3: EVIDe2400263, 2024

- Deneux-Tharaux, C., Kahn, E., Nazerali, H., Sokal, D. C.: Pregnancy rates after vasectomy: a survey of US urologists. Contraception, 69: 401, 2004

- Jamieson, D. J., Costello, C., Trussell, J. et al.: The risk of pregnancy after vasectomy. Obstet Gynecol, 103: 848, 2004

- Ha, A., Zhang, C. A., Li, S. et al.: A Contemporary Estimate of Vasectomy Failure in the United States: Analysis of US Claims Data. J Urol, 213: 638, 2025

- Romero, F. R., Romero, A. W., De Almeida, R. M. et al.: The significance of biological, environmental, and social risk factors for prostate cancer in a cohort study in brazil. Int Braz J Urol, 38: 769, 2012

- Goldacre, M. J., Wotton, C. J., Seagroatt, V., Yeates, D.: Cancer and cardiovascular disease after vasectomy: An epidemiological database study. Fertil Steril, 84: 1438, 2005

- Nayan, M., Hamilton, R. J., MacDonald, E. M. et al.: Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer: Population based matched cohort study. BMJ, 2016

- Jacobs, E. J., Anderson, R. L., Stevens, V. L. et al.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer incidence and mortality in a large US Cohort. J Clin Oncol, 34: 3880, 2016

- Shoag, J., Savenkov, O., Christos, P. J. et al.: Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer in a screening trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 26: 1653, 2017

- Tangen, C. M., Goodman, P. J., Till, C. et al.: Biases in recommendations for and acceptance of prostate biopsy significantly affect assessment of prostate cancer risk factors: Results from two large randomized clinical trials. J Clin Oncol, 34: 4338, 2016

- Byrne, K. S., Castaño, J. M., Chirlaque, M. D. et al.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). J Clin Oncol, 35: 1297, 2017

- Davenport, M. T., Zhang, C. A., Leppert, J. T. et al.: Vasectomy and the risk of prostate cancer in a prospective US Cohort: Data from the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Andrology, 7: 178, 2019

- Sidney, S., Quesenberry Jr, C. P., Sadler, M. C. et al.: Vasectomy and the risk of prostate cancer in a cohort of multiphasic health-checkup examinees: second report. Cancer Causes Control, 2: 113, 1991

- Nair-Shalliker, V., Bang, A., Egger, S. et al.: Family history, obesity, urological factors and diabetic medications and their associations with risk of prostate cancer diagnosis in a large prospective study. Br J Cancer, 127: 735, 2022

- Mucci, L. A., Siddiqui, M. M., Wilson, K. M. et al.: Vasectomy and risk of lethal prostate cancer: A 24-year prospective study. J Clin Oncol, 31, 2013

- Husby, A., Wohlfahrt, J., Melbye, M.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer risk: A 38-year nationwide cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst, 112: 71, 2020

- Eisenberg, M. L., Li, S., Brooks, J. D. et al.: Increased risk of cancer in infertile men: Analysis of U.S. claims data. J Urol, 193: 1596, 2015

- Giovannucci, E., Ascherio, A., Rimm, E. B. et al.: A prospective cohort study of vasectomy and prostate cancer in US men. JAMA, 269: 873, 1993

- Giovannucci, E., Tosteson, T. D., Speizer, F. E. et al.: A retrospective cohort study of vasectomy and prostate cancer in US men. JAMA, 269: 878, 1993

- Rohrmann, S., Paltoo, D. N., Platz, E. A. et al.: Association of vasectomy and prostate cancer among men in a Maryland cohort. Cancer Causes Control, 16: 1189, 2005

- Rosenberg, L., Palmer, J. R., Zauber, A. G. et al.: The relation of vasectomy to the risk of cancer. Am J Epidemiol, 140: 431, 1994

- Mettlin, C., Natarajan, N., Huben, R.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol, 132: 1056, 1990

- Cox, B., Sneyd, M. J., Paul, C. et al.: Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer. JAMA, 287: 3110, 2002

- Di, H., Wen, Y.: Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer: A Mendelian randomization study and confounder analysis. Prostate, 84: 269, 2024

- Holt, S. K., Salinas, C. A., Stanford, J. L.: Vasectomy and the risk of prostate cancer. J Urol, 180: 2565, 2008

- Lesko, S. M., Louik, C., Vezina, R. et al.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer. J Urol, 161: 1848, 1999

- Patel, D. A., Bock, C. H., Schwartz, K. et al.: Sexually transmitted diseases and other urogenital conditions as risk factors for prostate cancer: A case-control study in Wayne County, Michigan. Cancer Causes Control, 16: 263, 2005

- John, E. M., Whittemore, A. S., Wu, A. H. et al.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer: Results from a multiethnic case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst, 87: 662, 1995

- Stanford, J. L., Wicklund, K. G., McKnight, B. et al.: Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 8: 881, 1999

- Hayes, R. B., Pottern, L. M., Greenberg, R. et al.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer in US blacks and whites. Am J Epidemiol, 137: 263, 1993

- Lightfoot, N., Conlon, M., Kreiger, N. et al.: Medical history, sexual, and maturational factors and prostate cancer risk. Ann Epidemiol, 14: 655, 2004

- Schwingl, P. J., Meirik, O., Kapp, N., Farley, T. M.: Prostate cancer and vasectomy: a hospital-based case-control study in China, Nepal and the Republic of Korea. Contraception, 79: 363, 2009

- Platz, E. A., Yeole, B. B., Cho, E. et al.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer: A case-control study in India. Int J Epidemiol, 26: 933, 1997

- Hennis, A. J., Wu, S. Y., Nemesure, B., Leske, M. C.: Urologic characteristics and sexual behaviors associated with prostate cancer in an African-Caribbean population in Barbados, West Indies. Prostate Cancer, 2013: 682750, 2013

- Sunny, L.: Is it reporting bias doubled the risk of prostate cancer in vasectomised men in Mumbai, India? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 6: 320, 2005

- Emard, J. F., Drouin, G., Thouez, J. P., Ghadirian, P.: Vasectomy and prostate cancer in Québec, Canada. Health Place, 7: 131, 2001

- Dekkers, O. M., Vandenbroucke, J. P., Cevallos, M. et al.: COSMOS-E: Guidance on conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies of etiology. PLoS Med, 16: e1002742, 2019

- Weinmann, S., Shapiro, J. A., Rybicki, B. A. et al.: Medical history, body size, and cigarette smoking in relation to fatal prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control, 21: 117, 2010

- Coady, S. A., Sharrett, A. R., Zheng, Z. J. et al.: Vasectomy, inflammation, atherosclerosis and long-term followup for cardiovascular diseases: No associations in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J Urol, 167: 204, 2002

- Manson, J. E., Ridker, P. M., Spelsberg, A. et al.: Vasectomy and subsequent cardiovascular disease in US physicians. Contraception, 59: 181, 1999

- Schuman, L. M., Coulson, A. H., Mandel, J. S. et al.: Health status of American men--A study of post-vasectomy sequelae. J Clin Epidemiol, 46: 697, 1993

- Kronmal, R. A., Krieger, J. N., Coxon, V. et al.: Vasectomy is associated with an increased risk for urolithiasis. Am J Kidney Dis, 29: 207, 1997

- Lightner, D. J., Wymer, K., Sanchez, J., Kavoussi, L.: Best Practice Statement on Urologic Procedures and Antimicrobial Prophylaxis. J Urol, 203: 351, 2020

- Berrios-Torres, S. I., Umscheid, C. A., Bratzler, D. W. et al.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surg, 152: 784, 2017

- Tanner, J., Melen, K.: Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 8: CD004122, 2021

- Grober, E. D., Domes, T., Fanipour, M., Copp, J. E.: Preoperative hair removal on the male genitalia: clippers vs. razors. J Sex Med, 10: 589, 2013

- Aggarwal, H., Chiou, R. K., Siref, L. E., Sloan, S. E.: Comparative analysis of pain during anesthesia and no-scalpel vasectomy procedure among three different local anesthetic techniques. UROLOGY, 74: 77, 2009

- Joukhadar, N., Lalonde, D.: How to Minimize the Pain of Local Anesthetic Injection for Wide Awake Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open, 9: e3730, 2021

- Shih, G., Njoya, M., Lessard, M., Labrecque, M.: Minimizing pain during vasectomy: the mini-needle anesthetic technique. J Urol, 183: 1959, 2010

- Younis, I., Bhutiani, R. P.: Taking the 'ouch' out - effect of buffering commercial xylocaine on infiltration and procedure pain - A prospective, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Ann R Coll Surg Engl, 86: 213, 2004

- Cooper, T. P.: Use of EMLA cream with vasectomy. Urology, 60: 135, 2002

- De Lichtenberg, M. H., Krogh, J., Rye, B., Miskowiak, J.: Topical anesthesia with eutetic mixture of local anesthetics cream in vasectomy: 2 randomized trials. J Urol, 147: 98, 1992

- Robles J, A. N., Brummett C, et al.: Rationale and Strategies for Reducing Urologic Post-Operative Opioid Prescribing: American Urological Association, 2021

- Casey, R., Zadra, J., Khonsari, H.: A comparison of etodolac (Ultradol®) with acetaminophen plus codeine (Tylenol 3) in controlling post-surgical pain in vasectomy patients. Curr Med Res Opin, 13: 555, 1997

- Manson, A. L.: Trial of ibuprofen to prevent post-vasectomy complications. J Urol, 139: 965, 1988

- Mehta, A., Hsiao, W., King, P., Schlegel, P. N.: Perioperative celecoxib decreases opioid use in patients undergoing testicular surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol, 190: 1834, 2013

- Li, S. Q., Goldstein, M., Zhu, J., Huber, D.: The no-scalpel vasectomy. J Urol, 145: 341, 1991

- Nirapathpongporn, A., Huber, D. H., Krieger, J. N.: No-scalpel vasectomy at the King's birthday vasectomy festival. Lancet, 335: 894, 1990

- Sokal, D., McMullen, S., Gates, D., Dominik, R.: A comparative study of the no scalpel and standard incision approaches to vasectomy in 5 countries. The Male Sterilization Investigator Team. J Urol, 162: 1621, 1999

- Sandhu, A. S., Kao, P. R.: Comparative evaluation of no-scapel vasectomy and standard incisional vasectomy. Med J Armed Forces India, 54: 32, 1998

- Alderman, P. M., Morrison, G. E.: Standard incision or no-scalpel vasectomy? J Fam Pract, 48: 719, 1999

- Skriver, M., Skovsgaard, F., Miskowiak, J.: Conventional or Li vasectomy: A questionnaire study. Br J Urol, 79: 596, 1997

- Holt, B. A., Higgins, A. F.: Minimally invasive vasectomy. Br J Urol, 77: 585, 1996

- Chen, K. C., Peng, C. C., Hsieh, H. M., Chiang, H. S.: Simply modified no-scalpel vasectomy (percutaneous vasectomy)--a comparative study against the standard no-scalpel vasectomy. Contraception, 71: 153, 2005

- Chen, K. C.: A novel instrument-independent no-scalpel vasectomy - a comparative study against the standard instrument-dependent no-scalpel vasectomy. Int J Androl, 27: 222, 2004

- Jouannet, P., David, G.: Evolution of the properties of semen immediately following vasectomy. Fertil Steril, 29: 435, 1978

- Lewis, E. L., Brazil, C. K., Overstreet, J. W.: Human sperm function in the ejaculate following vasectomy. Fertil Steril, 42: 895, 1984

- Richardson, D. W., Aitken, R. J., Loudon, N. B.: The functional competence of human spermatozoa recovered after vasectomy. J Reprod Fertil, 70: 575, 1984

- Black, T., Francome, C.: The evolution of the Marie Stopes electrocautery no-scalpel vasectomy procedure. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care, 28: 137, 2002

- Black, T. R., Gates, D. S., Lavely, K., Lamptey, P.: The percutaneous electrocoagulation vasectomy technique--a comparative trial with the standard incision technique at Marie Stopes House, London. Contraception, 39: 359, 1989

- Sokal, D., Irsula, B., Chen-Mok, M. et al.: A comparison of vas occlusion techniques: cautery more effective than ligation and excision with fascial interposition. BMC Urol, 4: 12, 2004

- Sokal, D., Irsula, B., Hays, M. et al.: Vasectomy by ligation and excision, with or without fascial interposition: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN77781689]. BMC Med, 2: 6, 2004

- Barone, M. A., Irsula, B., Chen-Mok, M. et al.: Effectiveness of vasectomy using cautery. BMC Urol, 4: 10, 2004

- Labrecque, M., Hays, M., Chen-Mok, M. et al.: Frequency and patterns of early recanalization after vasectomy. BMC Urol, 6: 25, 2006

- Labrecque, M., Nazerali, H., Mondor, M. et al.: Effectiveness and complications associated with 2 vasectomy occlusion techniques. J Urol, 168: 2495, 2002

- Moss, W. M.: A comparison of open-end versus closed-end vasectomies: A report on 6220 cases. Contraception, 46: 521, 1992

- Li, S. Q., Xu, B., Hou, Y. H. et al.: Relationship between vas occlusion techniques and recanalization. Adv Contracept Deliv Syst, 10: 153, 1994

- Shakeri, S., Aminsharifi, A. R., Khalafi, M.: Fascial interposition technique for vasectomy: Is it justified? Urol Int, 82: 361, 2009

- Li, S. Q., Xu, B., Hou, Y. H. et al.: Relationship between vas occlusion techniques and recanalization. Adv Contracept Deliv Syst, 10: 153, 1994

- Lai, H. H., Pontari, M. A., Argoff, C. E. et al.: Male Chronic Pelvic Pain: AUA Guideline: Part III Treatment of Chronic Scrotal Content Pain. J Urol, 214: 138, 2025

- Lawton, S., Hoover, A., James, G. et al.: Risk of post-vasectomy infections in 133,044 vasectomies from four international vasectomy practices. Int Braz J Urol, 49: 490, 2023

- Badrakumar, C., Gogoi, N. K., Sundaram, S. K.: Semen analysis after vasectomy: When and how many? BJU Int, 86: 479, 2000

- McMartin, C., Lehouillier, P., Cloutier, J. et al.: Can a Low Sperm Concentration without Assessing Motility Confirm Vasectomy Success? A Retrospective Descriptive Study. J Urol, 206: 109, 2021

- Welliver, C., Zipkin, J., Lin, B. et al.: Factors affecting post-vasectomy semen analysis compliance in home- and lab-based testing. Can Urol Assoc J, 17, 2023

- Punjani, N., Andrusier, M., Hayden, R. et al.: Home testing may not improve postvasectomy semen analysis compliance. Urol Pract, 8: 337, 2021

- Trussler, J., Browne, B., Merino, M. et al.: Post-vasectomy semen analysis compliance with use of a home-based test. Can J Urol, 27: 10388, 2020

- Zhu, E. Y. S., Saba, B., Bernstein, A. P. et al.: Providing a post-vasectomy semen analysis cup at the time of vasectomy rather than post-operatively improves compliance. Transl Androl Urol, 13: 72, 2024

- Atkinson, M., James, G., Bond, K. et al.: Comparison of postal and non-postal post-vasectomy semen sample submission strategies on compliance and failures: an 11-year analysis of the audit database of the Association of Surgeons in Primary Care of the UK. BMJ Sex Reprod Health, 48: 54, 2022

- Hancock, P., McLaughlin, E., British Andrology, S.: British Andrology Society guidelines for the assessment of post vasectomy semen samples (2002). J Clin Pathol, 55: 812, 2002

- Dohle, G. R., Meuleman, E. J., Hoekstra, J. W. et al.: [Revised guideline 'Vasectomy' from the Dutch Urological Association]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd, 149: 2728, 2005

- Bieniek, J. M., Fleming, T. B., Clark, J. Y.: Reduced postvasectomy semen analysis testing with the implementation of special clearance parameters. Urology, 86: 445, 2015

- Ouitrakul S, S. M., Treetampinich C, Choktanasiri W, Vallibhakara SA, Satirapod C: The effect of different timing after ejaculation on sperm motility and viability in semen analysis at room temperature. J Med Assoc Thai 101: 26, 2018

- Lombardi, C. V. L., J.; Han, W.; Vij, R.; Nadiminty, N.; Shah, T.A.; Sindhwani, P: Balancing Post-Vasectomy Adequate Sperm Clearance with Patient Compliance: Time to Rethink? Uro 4: 214, 2024

- Marwood, R. P., Beral, V.: Disappearance of spermatozoa from ejaculate after vasectomy. Br Med J, 1: 87, 1979

- Hendry, J., Small, R., Zreik, A. et al.: The case for early post-vasectomy semen analysis combining small non-motile sperm and azoospermia. J Clin Urol, 12: 50, 2019

- Smith, A. G., Crooks, J., Singh, N. P. et al.: Is the timing of post-vasectomy seminal analysis important? Br J Urol, 81: 458, 1998

- Edwards, I. S.: Earlier testing after vasectomy, based on the absence of motile sperm. Fertil Steril, 59: 431, 1993

- Bedford, J. M., Zelikovsky, G.: Viability of spermatozoa in the human ejaculate after vasectomy. Fertil Steril, 32: 460, 1979

- Labrecque, M., St-Hilaire, K., Turcot, L.: Delayed vasectomy success in men with a first postvasectomy semen analysis showing motile sperm. Fertil Steril, 83: 1435, 2005

- Brannigan, R. E., Hermanson, L., Kaczmarek, J. et al.: Updates to Male Infertility: AUA/ASRM Guideline (2024). J Urol, 212: 789, 2024

- Valerie, U., De Brucker, S., De Brucker, M. et al.: Pregnancy after vasectomy: surgical reversal or assisted reproduction? Hum Reprod, 33: 1218, 2018

- Ren, L. J., Xue, R. Z., Wu, Z. Q. et al.: Vasectomy reversal in China during the recent decade: insights from a multicenter retrospective investigation. Asian J Androl, 25: 416, 2023

- Holman, C. D., Wisniewski, Z. S., Semmens, J. B. et al.: Population-based outcomes after 28,246 in-hospital vasectomies and 1,902 vasovasostomies in Western Australia. BJU Int, 86: 1043, 2000

- Ghaed, M. A., Mahmoodi, F., Alizadeh, H. R.: Prognostic factors associated with bilateral, microsurgical vasovasostomy success. Middle East Fertil Soc J, 23: 373, 2018

- Farber, N. J., Flannigan, R., Srivastava, A. et al.: Vasovasostomy: kinetics and predictors of patency. Fertil Steril, 113: 774, 2020

- Davis, N. F., Gnanappiragasam, S., Nolan, W. J., Thornhill, J. A.: Predictors of live birth after vasectomy reversal in a specialist fertility centre. Ir Med J, 110: 495, 2017

- Gerrard, E. R., Jr., Sandlow, J. I., Oster, R. A. et al.: Effect of female partner age on pregnancy rates after vasectomy reversal. Fertil Steril, 87: 1340, 2007

- Belker, A. M., Thomas, A., Jr., Fuchs, E. F. et al.: Results of 1,469 microsurgical vasectomy reversals by the Vasovasostomy Study Group. J Urol Nurs, 11: 93, 1992

- Hinz, S., Rais-Bahrami, S., Kempkensteffen, C. et al.: Fertility rates following vasectomy reversal: importance of age of the female partner. Urol Int, 81: 416, 2008

- Ostrowski, K. A., Polackwich, A. S., Conlin, M. J. et al.: Impact on Pregnancy of Gross and Microscopic Vasal Fluid during Vasectomy Reversal. J Urol, 194: 156, 2015

- Hsiao, W., Goldstein, M., Rosoff, J. S. et al.: Nomograms to predict patency after microsurgical vasectomy reversal. J Urol, 187: 607, 2012

- Hsiao, W., Sultan, R., Lee, R., Goldstein, M.: Increased follicle-stimulating hormone is associated with higher assisted reproduction use after vasectomy reversal. J Urol, 185: 2266, 2011

- Cosentino, M., Peraza, M. F., Vives, A. et al.: Factors predicting success after microsurgical vasovasostomy. Int Urol Nephrol, 50: 625, 2018

- Vrijhof, H. J., Delaere, K. P.: Vasovasostomy results in 66 patients related to obstructive intervals and serum agglutinin titres. Urol Int, 53: 143, 1994

- Bolduc, S., Fischer, M. A., Deceuninck, G., Thabet, M.: Factors predicting overall success: a review of 747 microsurgical vasovasostomies. Can Urol Assoc J, 1: 388, 2007

- Ramasamy, R., Mata, D. A., Jain, L. et al.: Microscopic visualization of intravasal spermatozoa is positively associated with patency after bilateral microsurgical vasovasostomy. Andrology, 3: 532, 2015

- Ory, J., Nackeeran, S., Blankstein, U. et al.: Predictors of success after bilateral epididymovasostomy performed during vasectomy reversal: A multi-institutional analysis. Can Urol Assoc J, 16: E132, 2022

- Safarinejad, M. R., Lashkari, M. H., Asgari, S. A. et al.: Comparison of macroscopic one-layer over number 1 nylon suture vasovasostomy with the standard two-layer microsurgical procedure. Hum Fertil (Camb), 16: 194, 2013

- Amjadi, M., Jahantabi, E., Nouri, H. et al.: One-layer macroscopic verus two-layer microscopic vasovasostomy: Our experience in two referral hospitals. Urologia, 90: 322, 2023

- Wang, B., Liu, Z., Jiang, H.: Comparison of low-power magnification one-layer vasovasostomy with stent and microscopic two-layer vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal. Int J Impot Res, 32: 617, 2020

- Fischer, M. A., Grantmyre, J. E.: Comparison of modified one- and two-layer microsurgical vasovasostomy. BJU Int, 85: 1085, 2000

- Nyame, Y. A., Babbar, P., Almassi, N. et al.: Comparative cost-effectiveness analysis of modified 1-layer versus formal 2-layer vasovasostomy technique. J Urol, 195: 434, 2016

- Parekattil, S. J., Gudeloglu, A., Brahmbhatt, J. et al.: Robotic assisted versus pure microsurgical vasectomy reversal: Technique and prospective database control trial. J Reconstr Microsurg, 28: 435, 2012

- Schiff, J., Chan, P., Li, P. S. et al.: Outcome and late failures compared in 4 techniques of microsurgical vasoepididymostomy in 153 consecutive men. J Urol, 174: 651, 2005

- Degraeve, A., Tosco, L., Tombal, B. et al.: Definition of a European pre-vasectomy scoring system to identify patients at risk of vasectomy regret. Sex Med, 12: qfae094, 2024

- Britton, L. E., Alspaugh, A., Greene, M. Z., McLemore, M. R.: CE: An Evidence-Based Update on Contraception. Am J Nurs, 120: 22, 2020

- Bradshaw, A., Ballon-Landa, E., Owusu, R., Hsieh, T. C.: Poor Compliance With Postvasectomy Semen Testing: Analysis of Factors and Barriers. Urology, 136: 146, 2020

- Ward, B., Sellke, N., Rhodes, S. et al.: Driving Time and Compliance With Postvasectomy Semen Analysis Drop-Off. Urology, 184: 1, 2024

- Pelzman, D., Honig, S., Sandlow, J.: Comparative review of vasectomy guidelines and novel vasal occlusion techniques. Andrology, 12: 1541, 2024

- Wang, C., Meriggiola, M. C., Amory, J. K. et al.: Practice and development of male contraception: European Academy of Andrology and American Society of Andrology guidelines. Andrology, 12: 1470, 2024

- Bania, J., Wrona, J., Fudali, K. et al.: Male Hormonal Contraception-Current Stage of Knowledge. J Clin Med, 14, 2025

- Howard, S. A., Benhabbour, S. R.: Non-Hormonal Contraception. J Clin Med, 12, 2023

- Khilwani, B., Badar, A., Ansari, A. S., Lohiya, N. K.: RISUG((R)) as a male contraceptive: journey from bench to bedside. Basic Clin Androl, 30: 2, 2020

- Sharlip, I. D., Belker, A. M., Honig, S. et al.: Vasectomy: AUA guideline. J Urol, 188: 2482, 2012

- Altok, M., Sahin, A. F., Divrik, R. T. et al.: Prospective comparison of ligation and bipolar cautery technique in non-scalpel vasectomy. Int Braz J Urol, 41: 1172, 2015